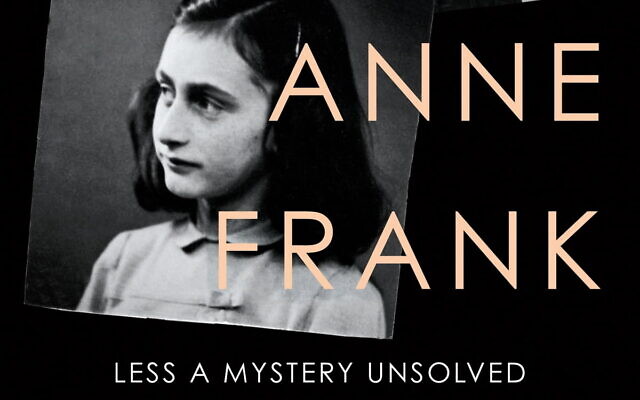

New Book Names Alleged Betrayer of Anne Frank

A new investigation claims that a fellow Jew was responsible for alerting the Nazis to the Franks’ hiding place. Historians have cast doubt on its conclusions.

Any story focused on Anne Frank, the young Jewish diarist who hid from the Nazis with her family for nearly two years in an Amsterdam attic, is sure to garner headlines. The recent publication of a book and release of a “60 Minutes” segment purporting to name the Frank family’s alleged betrayer has certainly stoked controversy in the Jewish community.

“For many people, Anne Frank represents the Holocaust,” said Sally N. Levine, executive director of the Georgia Commission on the Holocaust. “For many, it’s their introduction to the Holocaust.”

That’s because “The Diary of a Young Girl,” first published in 1947, is often read by students in middle school. The book documents Frank’s experiences from 1942, when she started writing her diary, to 1944, when her family was discovered by the Nazis and deported to Auschwitz, and eventually, with her sister, Margot, to Bergen-Belsen, where they both died.

Of the eight people who had hidden behind the famous bookcase in Amsterdam, only Otto Frank, Anne’s father and owner of the office below, survived the Holocaust. Otto Frank retained possession of his daughter’s diary when he returned to the annex after the Allies defeated the Nazis.

According to a recently published book, “The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation” by Rosemary Sullivan, an anonymous letter sent to Otto Frank after the war claimed that Jewish businessman Arnold van den Bergh, a member of the Nazi-appointed Jewish Council, was responsible for alerting the Nazis to the Franks’ hiding place.

Both the “60 Minutes” episode and the book are based on an investigation conducted by some four dozen consultants and crime experts, led by retired FBI investigator Vincent Pankoke. Artificial intelligence was used to sort through documents and records.

“Except for that anonymous note” to Otto Frank, “there’s no concrete evidence” that points to van den Bergh, said Levine, who acknowledged that she is a Holocaust educator, not a professional historian.

Still, Holocaust historians around the world have cast doubt on the investigation’s conclusions. According to the Times of Israel, all of the Dutch historians who were interviewed expressed “disappointment that resources were used on an investigation that produced ‘rubbish,’” as one researcher put it.

Reuters reported that the book’s Dutch publisher, Ambo Anthos, suspended printing of the book after questions were raised about the investigation and its conclusions.

And, although the Jewish community has requested that the book’s U.S. publisher, Harper Collins, pull the book it released in January, Tina Andreadis, a spokeswoman for the publisher, said in a Feb. 3 email to the AJT that “at this time, our publishing remains on track. While we recognize the strong reaction to the findings, the investigation was done with respect and the utmost care for an extremely sensitive topic.”

In the “60 Minutes” segment, FBI investigator Pankoke acknowledged that he would not have taken the results of his investigation to a prosecutor. He referred to the conclusions as “circumstantial,” containing “reasonable doubt.” However, he also stated that what his team discovered was “pretty convincing.”

The allegations against van den Bergh stem from his involvement with the Jewish Council. It is alleged that the council, which was an administrative body established by the Nazis to organize and oversee the Jewish community in the occupied city, kept lists of addresses where Jews were in hiding. Allegedly, van den Bergh handed over a list containing the Franks’ hiding place to the Nazis in return for the freedom of his family.

However, historians assert that van den Bergh, his wife and their three daughters were already in hiding in separate safehouses by 1944, when the Franks were discovered. The Times of Israel and other publications have quoted van den Bergh’s descendants arguing that he was not the Franks’ betrayer and expressing offense at the allegations.

According to the Times of Israel, a family friend of the van den Berghs, whose grandfather hid one of his daughters between 1943 and 1945, said that Arnold van den Bergh went into hiding not far from Amsterdam and that it would not have made sense for him to leave his hiding place to inform the Nazis of the Franks’ location.

Levine and other Holocaust educators contend that blaming van den Bergh is akin to “Holocaust inversion,” blaming the victim — in this case, a Jew — instead of the perpetrators of the Holocaust. She noted that members of Jewish councils in occupied countries “faced choiceless choices.” But, she added, it would have been “so dangerous” for the local Jewish Council to have such lists, that it makes this version of the story “hard to believe.”

comments