Breman Exhibit Connects Jews With Jazz

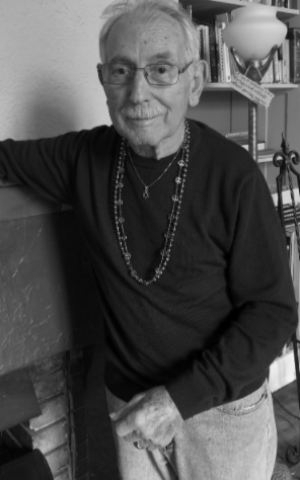

The iconic photographs of Herb Snitzer chronicle an important era in American life.

Herb Snitzer always seemed to have a knack of making the most of his opportunities in life. A day after he graduated art school in 1957 at the age of 23, he moved to New York to launch his career as a professional photographer. About a year later he was the photo editor of Metronome magazine, a job that put him at the center of New York’s thriving jazz scene.

Many of Snitzer’s photos of that time, including his portraits of Louis Armstrong, Jimmy Rushing and Miles Davis, are classics.

Now 64 years later, after a long and successful career, the William Breman Jewish Heritage Museum has brought together 80 of Snitzer’s best photographs in a retrospective called, “A Jazz Memoir: Photography of Herb Snitzer.”

Jazz artist Joe Alterman remembers as a youngster seeing Snitzer’s iconic image of the pianist Thelonious Monk and having it be a turning point in his life.

“I remember being a young kid and seeing that picture he did of Thelonious Monk with the piano, reflecting on his glasses and saying, ‘Who is this guy? I want to hear his music.’ So to me, I’ve always been aware of Herb’s work and his work has kind of turned me on to a lot of the music that I really love.”

Among the other famous pictures is one of Louis Armstrong taken while he was on the road with his sextet in 1960 in The Berkshires.

Around Armstrong’s neck was the gold star of David that the musician always wore. He had been given it by the Karnofsky family in New Orleans, who helped him buy his first trumpet when he worked for them as a boy. In a way the famous photograph seems to summarize the influence that Jews have had on the development of jazz over the past century.

Alterman, who is also executive director of Neranenah, the Atlanta Jewish music festival, has highlighted the connections Jews like Snitzer have made in the largely African American world of jazz, most importantly in the songs by Jewish composers that these musicians played.

“Jazz is black music. But without these songs, I don’t know where jazz would be,” Alterman said. “It’s like a gift that many Jewish composers gave to the great Black artists in our country. Black artists created the swing in the music, but a lot of the Jewish lyricists created the swing in the words, and it created an American language in song.”

That same sense of connection seems to be present in many of the photographs as well. According to the curator of the exhibit, Tony Casadonte, Snitzer and the artists he photographed achieved a very special sense of being a part of each other’s creative effort.

“There’s an intimacy to the images,” Casadonte told the AJT. “These people were performers. I think, as a photographer, Herb was in the moment and doing his performance and there’s almost like this collaborative effort. And I think that’s kind of the way jazz works. And I think that’s why these photographs work so well.”

Casadonte, whose Lumiere Gallery represents Snitzer in Atlanta and provided many of the images for the exhibit, believes that the late 1950s was an important time in American history, in the history of the civil rights movement. He feels that Snitzer and the magazine he worked for played a big part in what was happening then.

“Metronome magazine, which was the industry publication for jazz at the time, was very much about breaking down color barriers, breaking down some of these restrictive covenants that they would force performers to sign. Snitzer was right at the forefront of all of that.”

During a program at The Breman Museum, Alterman recalls being corrected when he introduced Snitzer as a photographer. “No,” Snitzer said, “I’m a visual historian.” He believed he was doing more than just taking pictures of musicians.

“That’s one of the major takeaways I have,” Alterman notes, “more than perhaps documenting jazz musicians, he wanted to elevate black artists. He thought that was the most important thing. What he would like is his legacy to be more than just: he took great photos of great musicians. He really did something to elevate Black musicians, who were really ignored and not given the respect that they really deserve in this country.”

The exhibit, which was scheduled to run for only three months last spring, has been extended to run in a virtual format until the end of March.

It can be viewed on The Breman website in an enhanced interactive format that the museum hopes to use to help create a unique online environment for future projects.

comments