Brett Kavanaugh and Leo Frank

We are morally bound to judge every person on the particular facts of his or her case.

Whatever we may think of Brett Kavanaugh’s views, his temperament or his appointment, we are morally bound to judge every person on the particular facts of his or her case – no matter how just is the cause that looms against that person. The analogy that we may miss is Leo Frank.

First Kavanaugh. His accuser, Dr. Ford, represents all those fighting against, and/or victimized by, the endemic subjugation of one gender by another – a horror historically and routinely punctuated by brute violence upon female bodies. The cause could not be more just. And Kavanaugh fits the opposite profile: a member of the subjugating gender, groomed to power from prep school, through college and law school, into the White House, onto the bench, and so forth.

Echoing Maine’s Senator Collins in her Oct. 5 floor speech, I was “very disturbed by the allegations” against Kavanaugh but found “a lack of corroborating evidence no matter where you looked.” Even those whose memories are etched by an attack on their bodies may over time transfer some elements – even the identity of the perpetrator.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

Now Frank. As Jews, we may miss the underlying issues for several reasons. Once we categorize something as anti-Semitic we tend to stop analyzing. Sadly, the people we tend to denigrate most, and listen to least, are white Southern Christians, who were Frank’s major antagonists. And our natural focus on the second murder victim, Leo Frank, may distract us from the first, Mary Phagan.

She died in a simmering economic and political cauldron. The United States had long pursued a tariff policy that protected Northern manufacturing at the expense of Southern commodity production. In short, the South sold cotton and other crops low, but had to buy manufactured goods high.

One result endangered girls, in particular: the need to find work wherever you could get it. So, at 13 – the age when our daughters would be attending junior highs – Mary Phagan lived away from her Marietta home, down in Atlanta, to work in a factory. Her murder touched a raw nerve in all those wanting to eliminate child labor and the economically-forced separation of children from their parents, and to protect girls, in particular, from situations wrought with danger.

The accused was Frank, also with an opposite profile. Today he’d be called a One Percenter: Northern; college-educated (and Ivy, no less); erudite; and rich, at least compared to his employees.

I do not diminish the role in Frank’s conviction and murder of pure, unadulterated anti-Semitism. But the problems that triggered Atlanta’s horror a century ago were real, and the struggle against them was just. As in so many other times and places, we Jews were collateral damage.

Of course, when we weigh the particular, objective facts, Frank probably didn’t do it – and we would be certain, but for the primitive state of forensics back then. Kavanaugh has a stronger case than Leo Frank that he didn’t do it.

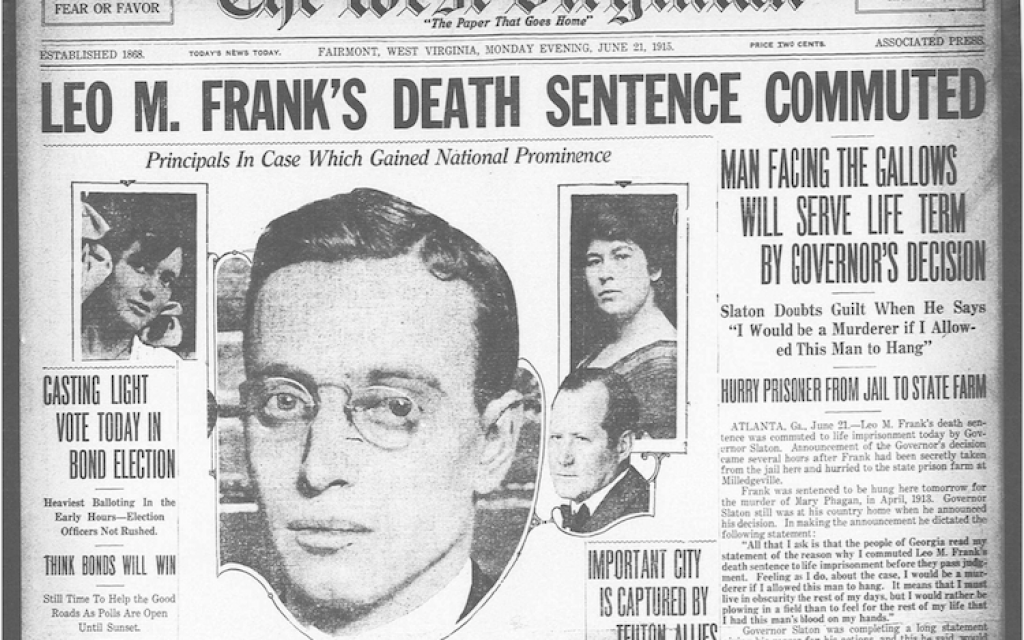

What happened after the initial accusations was similar: inflamed passions; a news media that fanned those flames; and hundreds of people roaming through public and private places needing to shout – or worse – more than to listen. Governor Slaton intervened for Frank – not to put him on the Supreme Court – just to commute a death sentence to life in prison. Slaton was run out of the state, after a mob had marched to the front door of his home demanding more immediate satisfaction. What will be Senator Collins’ fate?

In times like these, we Jews should stand in the forefront. We should let no cause, no matter how sacred, block us from particular facts in particular cases. As Senator Collins said: “In evaluating any given claim of misconduct, we will be ill-served in the long run if we abandon the presumption of innocence and fairness, tempting though it may be. We must always remember that it is when passions are most inflamed that fairness is most in jeopardy.”

We are constantly reminded in general to help the powerless, for example, Isaiah 1:17: “… seek justice, relieve the oppressed, judge the fatherless, plead for the widow.” But in the specific case we are admonished to keep our balance: “Ye shall do no unrighteousness in judgment; thou shalt not respect the person of the poor, nor favor the person of the mighty; but in righteousness shalt thou judge thy neighbor.” (Leviticus, 19:15).

Bill Rothschild is a native Atlantan who practices law, is a visiting Bible teacher at The Westminster Schools, and occasionally leads Torah study locally. He received rabbinic ordination at Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion and is the son of Rabbi Jacob Rothschild and Janice Rothschild Blumberg.

comments