Eizenstat Lecture Brings Holocaust Music to AA

"Hours of Freedom” offered new insights into what it meant to resist and defy attempts to suppress the human spirit during the Holocaust.

There is a Jewish mystical concept called klipot, encapsulated fragments of G-d’s light. When released and reunited through human kindness and good deeds, the hidden and fragmented light is made whole. This is akin to what Maestro Murry Sidlin has done in creating “Hours of Freedom: The Story of the Terezin Composer,” and The Defiant Requiem Foundation.

Atlanta native Ambassador Stuart E. Eizenstat, board chair of the Foundation, brought this moving and important performance to Ahavath Achim Synagogue in Buckhead Dec. 5. “Hours of Freedom” strives to offer new insights into what it meant to resist and defy attempts to suppress the human spirit during the Holocaust.

The Eizenstat Lecture series at Ahavath Achim Synagogue is currently in its 31st year and has hosted a cadre of notable personalities including Elie Wiesel, Natan Sharansky, Henry Kissinger, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Al Gore, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Joe Biden and two dozen others.

Events leading to this year’s “Hours of Freedom” originated from Rafael Schachter, a defiant, young Jewish Czech musician who smuggled in a score of Verdi’s Requiem Mass into the Theresienstadt concentration camp. There he organized choruses to sing for the weary workers imprisoned during World War II.

Edgar Krasa, a surviving member of the camp chorus who lived in Boston, told Sidlin, “We sang to the Nazis what we could not say to them.” The Verdi piece was performed 16 times during imprisonment, the last being for a tour of Red Cross leaders, complete with sham cookie and toy treats for the choral singing children, all of whom were sent to Auschwitz afterward.

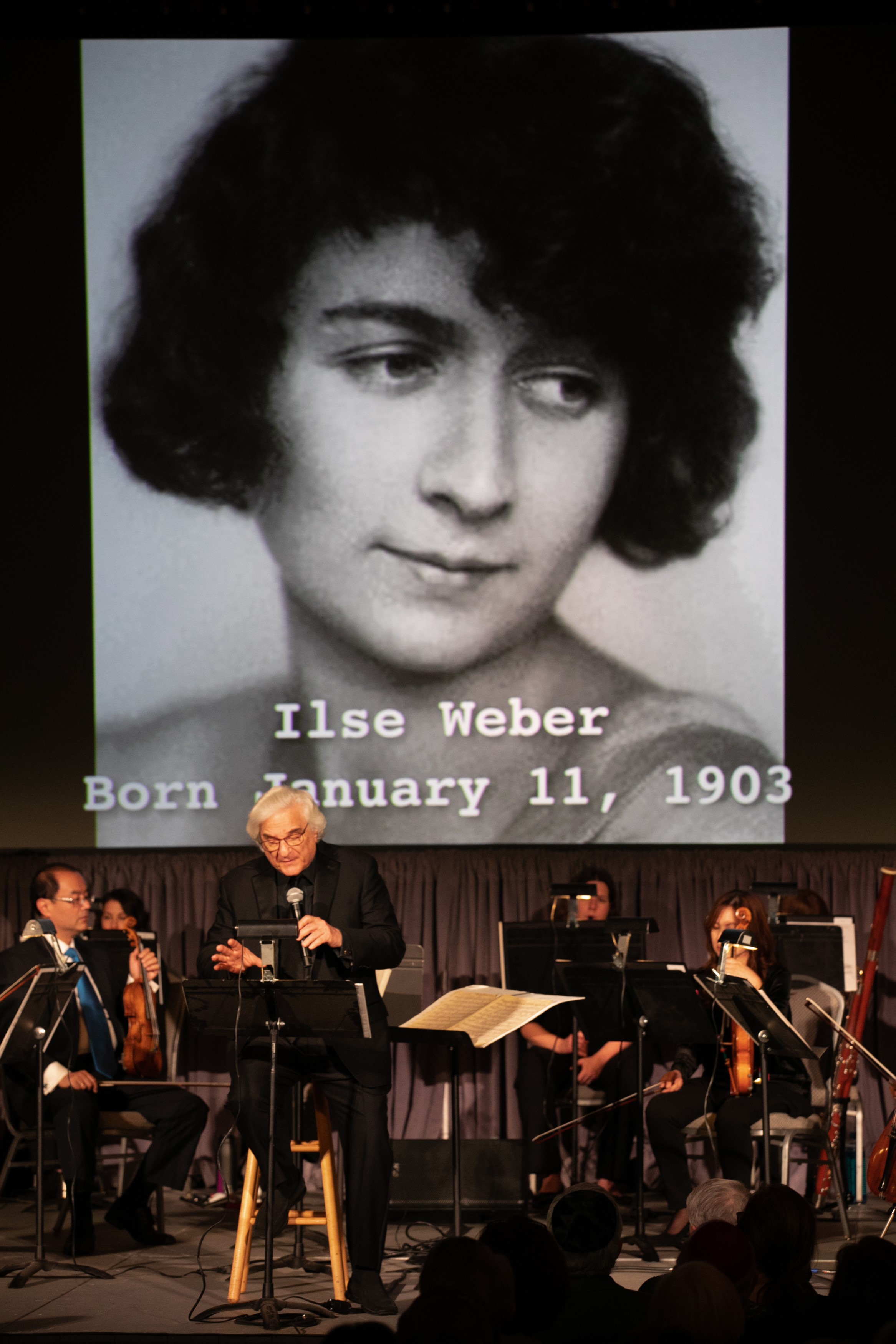

Sidlin met with Krasa and the other few surviving members of that Terezin chorus, who told him about the 15 composers in the camp who created music on scraps of paper (even toilet paper) and hid them in trash bins and walls, under floor boards and stuffed in the pockets of deported prisoners with the hope those individuals and the music they carried would survive.

“What you hear is what these composers could not hear, because they were killed,” Eizenstat stated bluntly. Sidlin searched out these scraps of music, hidden and fragmented like the ED, and deftly stitched them together to give us the “Hours of Freedom.” Upon hearing these hastily composed pieces, Sidlin used his imagination and some “speculative history” to create a nine-chapter program, dubbing them with titles such as “Longing,” “Hope,” “Broken Heart” and “Censorship,” all based upon his own impressions from the musical pieces.

Regarding “Hours of Freedom,” Eizenstat stresses that the “story belies the notion that Jews did not fight back in their own way. They used arts and music to keep dignity, spirit and hope alive” during Nazi oppression. He pointed out that only 10 of the 50 states have mandated Holocaust education; Georgia is not one of them. A primary purpose of The Defiant Requiem Foundation he chairs is to “use the concerts as a springboard for education; to teach the teachers.” To that end, these performance pieces have been edited into 45-minute classroom modules, intending to provide education within the current climate of rising anti-Semitism and Holocaust denial.

On one of those fateful scraps of paper, Krasa wrote, “When the experience is over, the tune, after all, rings in our ears.”

comments