German Refugees to Atlanta on U.S. Kindertransport

Among the 1,200 German Jewish children who fled before Kristallnacht were Jewish Atlantans. Those survivors and their families shared their stories with the AJT.

Just months before the earth-shattering tragedy of Kristallnacht occurred in Germany in November 1938, awakening the Jewish community to a new reality, the family of Heinz Birnbrei already knew their lives were endangered. The 14-year-old from Dortmund who was later to be known as Henry Birnbrey was given 24 hours to say goodbye to his parents and obtain his visa from the U.S. Consulate in Stuttgart. The future Atlantan sailed on the SS Hansa from Hamburg and arrived in New York in April 1938.

Birnbrey, now a father of four with 15 grandchildren and 21 great-grandchildren, never saw his parents again. His father was killed on Kristallnacht and his mother died a few months later. But thanks to the little-known U.S. version of the Kindertransport, his life was saved, as were about 1,200 other German Jewish children, including a handful who came to Atlanta.

According to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Birnbrey’s immigration was sponsored by the German-Jewish Children’s Aid, one of two organizations that helped coordinate the largest effort to bring children to the United States during World War II.

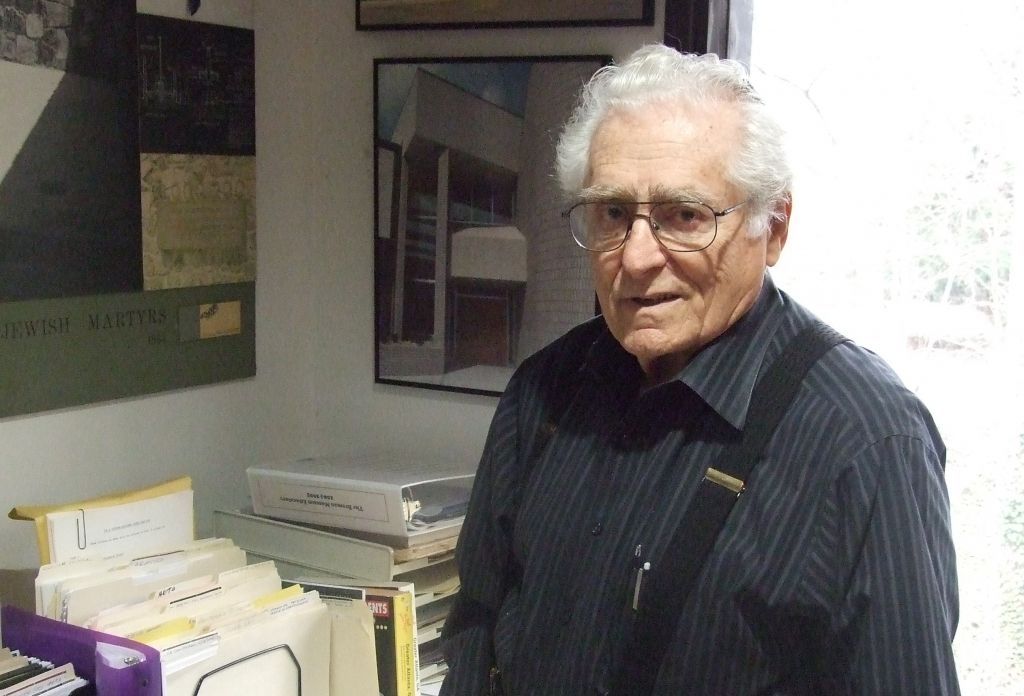

Birnbrey, who is about to celebrate his 96th birthday, told the AJT that from New York he went to Birmingham, Ala., with the help of the local chapter of the National Council of Jewish Women, and was there for nine months before coming to Atlanta, where he was a resident of the Hebrew Orphans’ Home for a while.

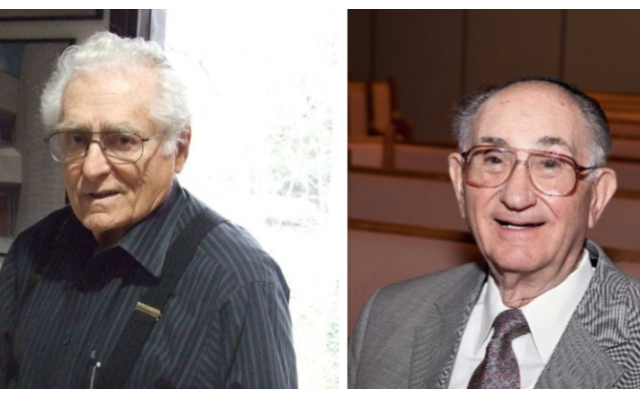

The late Frank Spiegel, who died last year, was one of five young Jewish men who arrived in New York and then was sent to a vocational school in Monroe, Ga., thanks to HIAS, then known as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.

Spiegel was born in Furth, Germany, the same city where Henry Kissinger was born, according to Spiegel’s son Mark. Spiegel was 17 years old when he arrived in the United States in 1937. He was sponsored by a relative in New York who helped him get a visa.

In his first years in Atlanta, he was assigned a case worker from a predecessor agency of Jewish Family & Career Services of Atlanta. “He’d meet with her periodically for guidance and she took copious notes, which are now stored at The Breman Museum,” Mark Spiegel said.

“After getting his first job at a filling station and attending the Georgia Institute of Technology, my father went into the Army. He was in boot camp where he met my mother, Helen, who was from Nuremberg,” Mark Spiegel told the AJT. Eventually, he saved enough money to bring his parents, brother and sister to the United States in 1941.

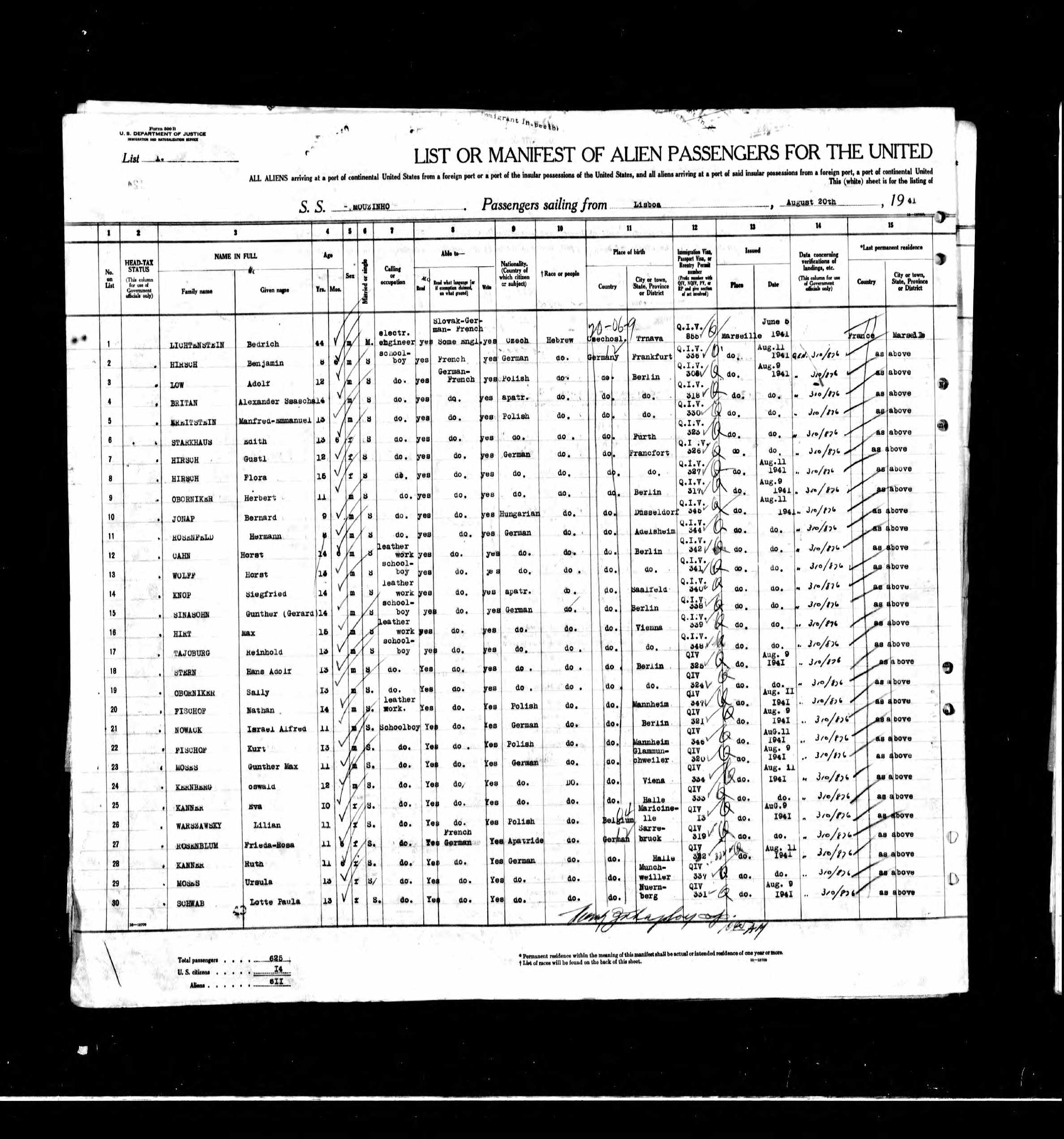

The late Benjamin Hirsch, who died early last year, arrived in New York from Lisbon in September 1941 with a group sponsored by the U.S. Committee for the Care of European Children on the SS Mouzinho, according to records from the U.S. Holocaust museum. Born in Frankfurt am Main, “he was accompanied on the ship by 49 other kids including his sisters Gustl and Flora. His brothers, Anselm and Jacob, were on an earlier transport that arrived in the U.S. in June 1941, carrying 100 kids,” with the help of the same organization. The Holocaust museum has a copy of Hirsch’s affidavit in lieu of a passport, issued in August 1941.

In 2000, American researcher Iris Posner created the organization, One Thousand Children, Inc., which represented and honored the experiences of unaccompanied refugee children. Posner named this group of children, the “One Thousand Children,” or OTC.

The term Kindertransport is most commonly used to refer to a British government-sponsored program in which immigration visa requirements were waived for some 12,000 refugee children. The situation was very different in the United States, where the children received no U.S. government visa immigration assistance.

According to an article on the Holocaust museum website about the OTC, “it is documented that the State Department deliberately made it very difficult for a Jewish refugee to get an entrance visa. And it was even harder to secure the appropriate papers for their parents, hence most had to remain in Europe.”

In 1939, Sen. Robert F. Wagner and Rep. Edith Rogers sponsored the Wagner-Rogers Bill in Congress, designed to admit 20,000 unaccompanied Jewish child refugees under the age of 14 into the country from Nazi Germany. However, the bill failed to get Congressional approval.

According to Birnbrey, “No one ever heard of the American Kindertransport.” It saved more than 1,000 lives, plus all their descendants, despite the harsh quota system for refugees coming from Europe.

Many of the dwindling number of survivors saved through the U.S. Kindertransport are not aware that the Holocaust museum has a service that collects information on Holocaust survivors, Andy Hollinger, director of communications, told the AJT. He suggested they check out www.ushmm.org/remember/resources-holocaust-survivors-victims.

comments