King’s Birmingham Jail Letter Through Jewish Lens

In Atlanta program Susannah Heschel discusses Judaism’s impact on the ideas that shaped the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

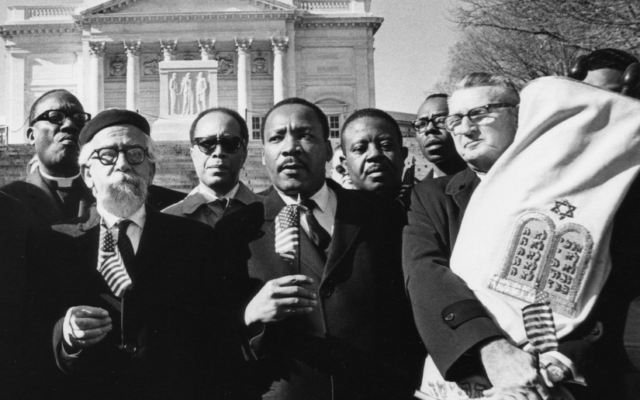

The significant role that Jewish religious leaders played during the civil right movement of the 1960s was highlighted in a discussion sponsored recently by The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta.

The discussion focused on King’s famous “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” written in 1965. Included in the program, that was presented online, were reflections by the late Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel daughter, Susannah Heschel.

Dr. Heschel is a Jewish Studies professor at Dartmouth College and an important figure in her own right. She mentions how her father’s writing, particularly his well-known volume on the ancient Hebrew prophets profoundly influenced King. He made the Hebrew Bible, “the central text of the civil rights movement,” she said.

“I think that what they, Dr. King and my father both understood, is that the message of the prophets is that God is full of passion and responds to us and God cares about us and God feels our suffering and feels that with us.”

Dr. Heschel went on to say that her father, who is generally recognized as one of the most important Jewish thinkers of the 20th century, considered the words of the prophets as a Divine command that charges us to be responsible for one another.

“Even though some are guilty of injustice, all of us are responsible for responding to injustice,” she said.

That teaching was particularly apparent in the open letter King wrote to his followers after being arrested for defying a court order not to lead a protest in Birmingham on Good Friday, April 12, 1965. He wrote his letter four days later from the Birmingham city jail. In it he outlined the basic principles of the nonviolent social protest movement that he led, and that people were morally responsible for defying unjust laws.

In his stand against the laws in the South that promoted racial segregation, King cited the contemporary Jewish theologian Martin Buber.

“All segregation statutes are unjust because segregation distorts the soul and damages the personality. It gives the segregator a false sense of superiority and the segregated a false sense of inferiority. To use the words of Martin Buber, the great Jewish philosopher, segregation substitutes an “I – it” relationship for the “I – thou” relationship and ends up relegating persons to the status of things.”

And he went on to cite the precedent for such action in the Book of Daniel of the Hebrew Bible.

“Of course, there is nothing new about this kind of civil disobedience. It was seen sublimely in the refusal of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego to obey the laws of Nebuchadnezzar because a higher moral law was involved.”

The Birmingham letter, which is said to have been inspired by an earlier suggestion that was made to him by Harvey Shapiro, the editor of The New York Times Magazine while King was imprisoned in Albany, Ga.

In Birmingham he was responding to a public appeal for “A Call for Unity” by eight local clergymen on the same day he was arrested. The religious leaders, who were all local racial moderates, felt that King’s actions were “untimely” and that Birmingham was about to experience “a new day” with a change in political leadership there.

One of those leaders was Rabbi Milton Grafman of Birmingham’s Temple Emanu-El, who had been leading the synagogue for almost 25 years and had been invited to the White House to discuss the racial situation in the city with President J.F. Kennedy.

But King rejected the suggestion by the rabbi and others, and he defended the nonviolent philosophy of his movement that “had no alternative, except of preparing for direct action.”

He wrote in his letter, “Whereby we would present our very bodies as a means of laying our case before the conscience of the local and national community.”

In the recent discussion, King’s daughter Bernice King, CEO of The King Center, said her father considered his call for nonviolent social action a mandate from God.

“My father urged us to think not only about how we as human beings understand God, but to look from God’s point of view. How does he look at us and see what creates this beautiful world? How, as wonderful human beings, do we behave toward one another’s point of view and experience, and to think about what our responsibility should be for God. So the issue for us, whether we’re Jews, Christians, Muslims, of course, is we need one another.”

Heschel believes that despite the prodding and protesting, that King was always looking for common ground when he wrote in his famous letter that “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny.”

She elaborated, “The civil rights movement was also an ecumenical movement. It brought in young Jews and rabbis, and I think restored our faith, restored our souls after the war. It gave us a sense of pride in our Bible and in our Judaism,”

- Bob Bahr

- Martin Luther King Jr.

- Civil Rights

- Atlanta

- Judaism

- Susannah Heschel

- The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change

- National Center for Civil and Human Rights

- Letter from Birmingham Jail

- Dartmouth College

- Martin Buber

- Birmingham Jail

- New York Times

- Bernice King

- Civil Rights Movement

- torah

comments