Opening Windows on Jewish Life Centuries Ago

Beth Tikvah audience told how 21st century technology makes the Cairo genizah accessible to a wider audience.

Dave Schechter is a veteran journalist whose career includes writing and producing reports from Israel and elsewhere in the Middle East.

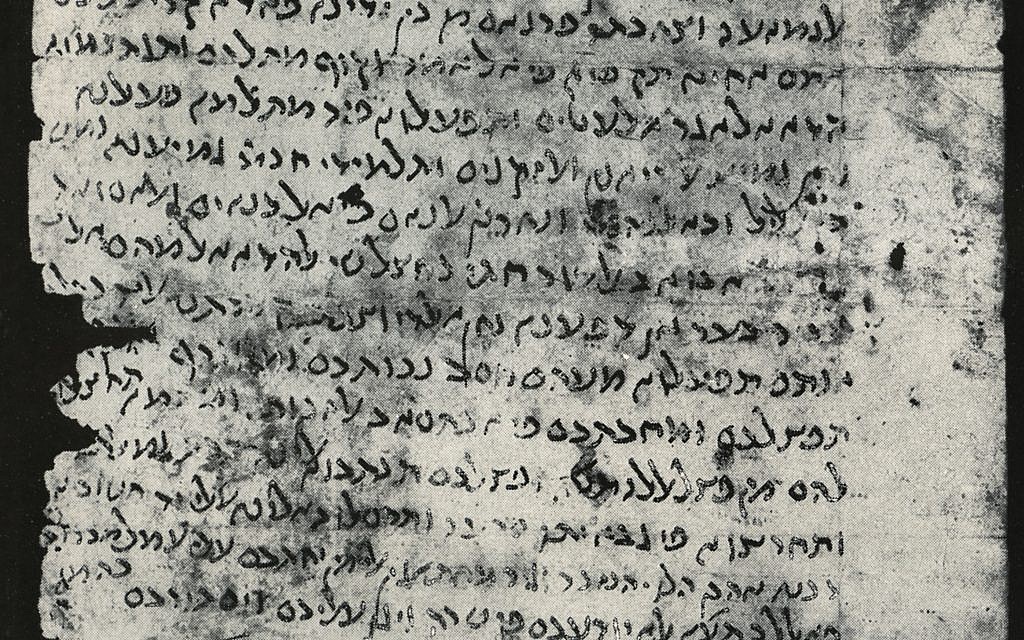

Think of an enormous jigsaw puzzle with 300,000 very old pieces, some dating as far back as the ninth century C.E.

Most of the pieces were created between the 10th-13th century, and are made of paper and vellum, though others are papyrus or cloth.

Some are small enough to fit in your palm, and even the larger ones are so fragile that they must be handled with care.

The writing on them, in Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic, Judeo-Arabic – Arabic written in Hebrew letters – and Judeo-Persian, ranges from the profound to the mundane.

There are works by Moses Maimonides, including portions of his Mishneh Torah and a draft of “The Guide for the Perplexed.”

And the doodling of a child learning the Hebrew alphabet, proving that Hebrew school has changed little.

There are love letters, bills of sale and pleas for justice.

These are the treasures of the Cairo genizah (“hiding place” in Hebrew).

Religious law required preserving sacred writings, particularly those mentioning G-d’s name, even contracts and letters, until they received a proper burial. These texts, and more secular material, filled the genizah, a room upstairs at the rear of the Ben Ezra Synagogue behind the women’s section, accessible only by ladder through a small door.

The synagogue is located in Fustat, in the old section of Cairo near where, as the story goes, the baby Moses was discovered adrift in a basket on the Nile River.

Why the material was not buried is not clear, but the genizah fragments – preserved in the arid Egyptian climate – are windows into the religious, commercial, political, social, cultural and family life of the Jewish community and its interactions with Christian and Moslem neighbors, over several hundred years.

The 10th to 12th centuries C.E. were the height of the Fatimid Caliphate, and Cairo was the capitol of an Islamic empire stretching throughout North Africa and the Middle East. In that period, as much as 90 percent of the world’s Jews may have lived in these lands.

The genizah’s existence was known in the 18th century, but toward the end of the 19th century a pair of adventurous and learned Scottish twins, Agnes Lewis and Margaret Gibson, made a crucial discovery.

A scrap the sisters purchased at a Cairo curio shop excited their friend Solomon Schechter, a Talmudic scholar at Cambridge University in England. Schechter (whose great-grandson authored this article) recognized it as a piece of the original Hebrew text of the “Book of Wisdom,” attributed to Ben Sira and dating to the second century B.C.E. Until then, it had been thought lost and available only in a Greek translation and known to Christians as Ecclesiastics.

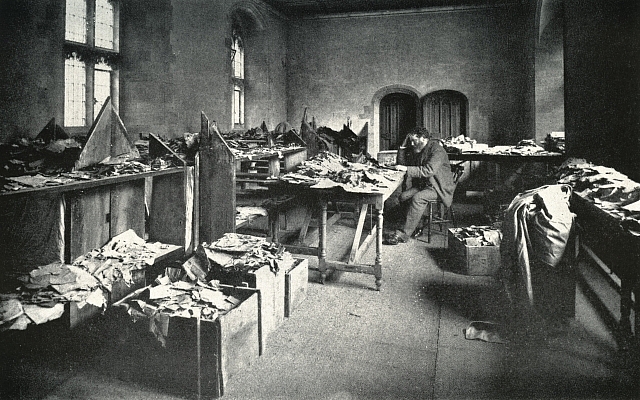

Schechter traveled to Egypt in 1896 and, after spending several weeks inhaling dust and sifting through piles upon piles of material, was granted permission by the Chief Rabbi of the Ben Ezra Synagogue to remove what he wished, and delivered crates containing 137,000 pieces to Cambridge University.

Schechter described the genizah this way: It is a battlefield of books, and the literary production of many centuries had their share in the battle, and their disjecta membra are now strewn over its area. Some of the belligerents have perished outright, and are literally ground to dust in the terrible struggle for space, whilst others, as if overtaken by a general crush, are squeezed into big unshapely lumps. … These lumps sometimes afford curiously suggestive combinations; as, for instance, when you find a piece of some rationalistic work, in which the very existence of either angels or devils is denied, clinging for its very life to an amulet in which these same beings (mostly the latter) are bound over to be on their good behaviour and not interfere with Miss Jair’s love for somebody. The development of the romance is obscured by the fact that the last lines of the amulet are mounted on some I.O.U., or lease, and this, in turn, is squeezed between the sheets of an old moralist, who treats all attention to money affairs with scorn and indignation. Again, all these contradictory matters cleave tightly to some sheets from a very old Bible.

Beginning 120 years ago, and for many decades after, the painstaking work of separating, sorting and classifying the puzzle pieces was done by hand at Cambridge, which has identified 193,000 individual items, and institutions worldwide with smaller collections. Cambridge has numbered and organized all of the pieces in its collection, and for half of the pieces has determined where the fragment was published, when and by whom.

In the 21st century, as several computer-generated projects around the world make an increasing number of the genizah fragments available online, new avenues of research open for historians and other scholars.

In some cases, puzzle pieces have been reunited digitally. A piece of a Passover haggadah in Cambridge was matched with one from a haggadah in a collection held by the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York.

Laura Newman Eckstein, until recently coordinator of Judaica Digital Humanities at University of Pennsylvania, came to Temple Beth Tikvah in Roswell to discuss how “crowdsourcing” online is expanding the pool of people working on the fragments beyond traditional academia.

Eckstein, whose extended family includes Beth Tikvah’s Cantor Nancy Kassel, is now pursuing a doctorate in early Atlanta Jewish history.

Her presentation included images of a 10th century shopping list, which included saffron and salmon, a marriage contract from Italy, and a haggadah written in Judeo-Persian, at the top of which were drawn pictures of goats.

A computer program constructed by a team at Penn, in collaboration with Zooniverse, an online research platform, allows “citizen scholars” to review the fragments. Since Penn’s “Scribes of the Cairo Geniza” project launched in August 2017, more than 3,700 volunteers have helped sort some 30,000 fragments.

Penn’s program endeavors to group the fragments by language, by whether the writing is script or print, by visual characteristics on the fragment, by whether the fragment might once have been bound, and by whether the subject might be formal (such as a contract) or informal (such as the shopping list).

“We wanted to see if people could begin to read these handwriting styles, to create some sort of online group so that people could begin to read these fragments,” Eckstein said.

In one case, Eckstein said, a woman recognized that the lined pattern on a fragment was not a religious symbol, but instead the design of a carpet, which she remembered from her grandfather, a carpet maker in Damascus, Syria.

As the project continues, the fragments “will live in a database, for scholars and non-scholars, alike,” Eckstein said.

The evidence of hundreds of years of Jewish life filled the Cairo Genizah. The inhabitants of that world could not have imagined the technology that is bringing them back to life, and showing how, in some ways, their concerns were not so dissimilar from those of today.

comments