Renowned Poet Joins Georgia Tech Poetry Department

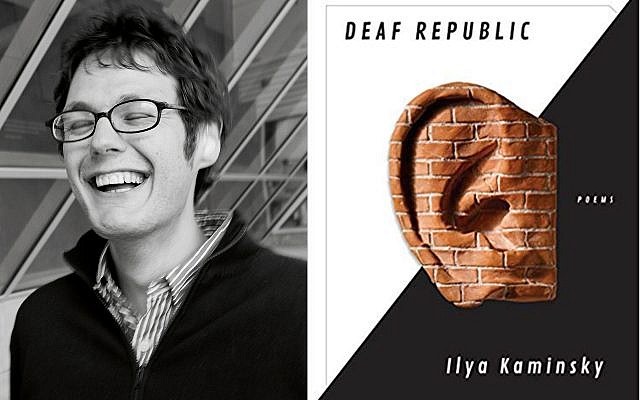

Ilya Kaminsky is an internationally praised poet, winner of numerous honors and awards and, most recently, was named Georgia Tech’s Bourne Poetry Chair.

Rachel is a reporter/contributor for the AJT and graduated from the University of Central Florida in Orlando. After post graduate work at Columbia University, she teaches writing at Georgia State and hosts/produces cable programming. She can currently be seen on Atlanta Interfaith Broadcasters.

Ilya Kaminsky is an internationally praised poet, winner of numerous honors and awards and, most recently, was named Georgia Tech’s Bourne Poetry Chair. He was raised in Odessa, Ukraine, the former Soviet Union.

At 4 years old, Kaminsky lost most of his hearing following a misdiagnosis. He arrived in the United States in 1993. He earned his Bachelor of Arts from Georgetown University and his law degree from the University of California.

He recently received the 2019 Creative Writing Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. We asked Kaminsky about his background and career.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

AJT: You began writing poetry in English?

Kaminsky: I wrote verses in Russian for quite some time before we came to America.

The question of English being my “preferred language for literature” would have been quite ironic back then, since none of us spoke English. But arriving in Rochester [N.Y.] was rather a lucky event. That place was a magical gift, it was like arriving to a writing colony, a Yaddo [N.Y. artist community] of sorts. There was nothing to do except for writing poetry!

My father died in 1994, a year after our arrival to America. I understood right away that it would be impossible for me to write about his death in the Russian language. … I choose English because no one in my family or friends knew it; no one I spoke to could read what I wrote. It was a parallel reality, an insanely beautiful freedom. It still is.

AJT: Has your language choice affected or influenced your writing?

Kaminsky: I find English to be a more precise language, while there are more possibilities for sound work in Russian.

In English, I write in lines. So the lines find their way on paper whether I overhear two boys insulting each other at the gas station, or see a gull cleaning her feet, or two old men playing dominoes on a hood of a car, or two young women kissing at the fish market. They become lines on receipts, on my hands, on a water bottle, on other people’s poems. Lines collect for years, but once in a while they discover that other lines are sexy and, well, the poems may come from that sort of a relationship.

AJT: Compare the experience of being Jewish in America to the Soviet Union?

Kaminsky: For me, it is cultural. I am a Soviet Jew. I left former USSR at 16, and that is the age at which people in that part of the world are quite formed in their outlooks on life. Of course, I can speak only for people of my generation who grew up in the 1990s and came of age watching their country fall apart and multiple ethnic conflicts flare up all along its perimeter.

I am a Jew whose holy books are Sholem Aleichem and Isaac Babel and Grace Paley and I.B. Singer and Bernard Malamud and great Medieval Jewish poets of Spain, and Bialik and Amichai and Kafka and Edmond Jabès and many other great Jewish authors of past and present.

In Odessa, being Jewish was, of course, also the question of language. Odessa Russian is very Yiddish-influenced language; it is quite different from Russian in Moscow or St. Petersburg.

Isaak Babel is the major writer who wrote in that language. As a child I first found Babel’s book on the kitchen table. That was before I wrote poems, or really even read books much, and finding it, I realized that the language my parents spoke, which was different from the language officials at my school spoke, was something that could be in a book.

In addition to that, being Jewish in the former USSR is quite different than being Jewish in this country. Here, it is a religion. There, it is an ethnicity identified in your passport. But even if somehow (which was the case for many people) in your passport it says that you are Russian, your neighbors still look you in the face and see exactly who you are. And when they hit you, they aim directly in your face. It is a very different world.

AJT: Has teaching with little to no hearing ever presented hurdles?

Kaminsky: I read lips. Over the years, I learned how to do it quite well. There is simply no other choice, so one adapts.

AJT: You’re also the new director of Poetry@Tech.

Kaminsky: Our goal is to provide access to the craft of poetry by bringing programs that hinge on diversity and foster understanding and community building through the arts.

This year alone we brought a famous poet from Belarus and a legendary poet who is also an award-winning human rights activist. We are bringing a Pulitzer Prize winner and MacArthur “Genius” Prize winner next year.

There are various other forms of public programming. For instance, we brought U.S. Poet Laureate Juan Felipe Herrera to local schools this spring.

We had a poet who lives in Hollywood come and speak about poetry and films. We had another poet speak about poetry and politics and another poet came to give a lecture on metaphors.

Additionally, Poetry@Tech also publishes Terminus, a literary magazine which does incredible work to publish such authors as Pulitzer Prize winners Vijay Seshadri, Billy Collins and Tyehimba Jess, among many other accomplished poets.

Such Atlanta poets as Theresa Davis and Katie Chaple, among others, have collaborated with Poetry@Tech to create outreach programs in Atlanta communities. As a part of this program, we also offer workshops at Positive Impact [Health Centers], bringing poetry to those living with HIV/AIDS.

Finally, in addition to Poetry@Tech, LMC [School of Literature Music and Communications] is also the home to Atlanta Review, the oldest existing journal in the American South to publish international literature.

AJT: Your newest book, “Deaf Republic,” deals with, among others, some modern political themes in a unique setting. Where did the inspiration come from?

Kaminsky: I did not have hearing aids until I was 16. As a deaf child, I experienced my country as a nation without sound. I heard USSR fall apart with my eyes.

Walking through the city, I watched the people; their ears were open all the time, they had no lids. I was interested in what the sounds might be like. The whooshing. The hissing. The whistle. The sound of keys turning in the lock, or water moving through the pipes two floors above us. I could easily notice how the people around me spoke to each other with their eyes without realizing it.

But what if the whole country was deaf like me? So that whenever a policeman’s commands were uttered, no one could hear? I liked to imagine that.

Through “Deaf Republic,” the townspeople teach each other sign language (illustrated in the book) as a way to coordinate, while remaining unintelligible to the government.

Although this book is a fable, in the center of it you will find a young man shot by police in the open street lying for hours on the pavement behind a police tape.

As Americans we seem to keep pretending that history is something that happens elsewhere, a misfortune that befalls other people. But history is lying there in the middle of our street, right behind the yellow police tape showing us who we are.

comments