The American Citizen

A fictional president of the United States once said: “America isn’t easy. America is advanced citizenship. You gotta want it bad, ’cause it’s gonna put up a fight. It’s gonna say, ‘You want free speech? Let’s see you acknowledge a man whose words make your blood boil, who’s standing center stage and advocating, at the top of his lungs, that which you would spend a lifetime opposing at the top of yours.’ ”

A fictional president of the United States once said: “America isn’t easy. America is advanced citizenship. You gotta want it bad, ’cause it’s gonna put up a fight. It’s gonna say, ‘You want free speech? Let’s see you acknowledge a man whose words make your blood boil, who’s standing center stage and advocating, at the top of his lungs, that which you would spend a lifetime opposing at the top of yours.’ ”

America isn’t easy, but even with its flaws, this 239-year-old experiment in self-governance remains the gold standard for people living in lesser forms of rule around the world.

America is advanced citizenship, yet too many Americans appear not to want it bad enough. They complain loudly but fail to utilize the tool so valuable that people around the world risk their lives in hopes of achieving it: the right to vote.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

These days, American citizenship is putting up one hell of a fight. Blood is boiling, and we’re still more than 10 months from Election Day on Nov. 8, 2016.

The teenager at home recently asked if this would be the most important presidential election in the nation’s history.

Every presidential election is the most important, I told him.

The sound and fury on and off the campaign trail signify that this election will be a referendum of sorts on American values: the role of immigrants in shaping and reshaping this country’s future; when to rely on diplomacy and when to deploy the armed forces; the responsibilities of corporations to their employees; honoring the lives of our elders and educating our children; and the balance between protecting the homeland and safeguarding civil liberties.

These are complicated issues. Demagoguery, slogans, labels, applause lines and provocative appeals — from any point on the political spectrum — are attempts to offer simple, comforting answers where none exists.

I recalled the words of that fictional president after the most recent gathering of our dinner and discussion group.

The seven dozen homemade latkes we brought were devoured by Jew and gentile alike. On that first night of Chanukah, the most learned among us explained the story behind lighting a menorah and the accompanying prayers, which those of us who are Jewish then chanted.

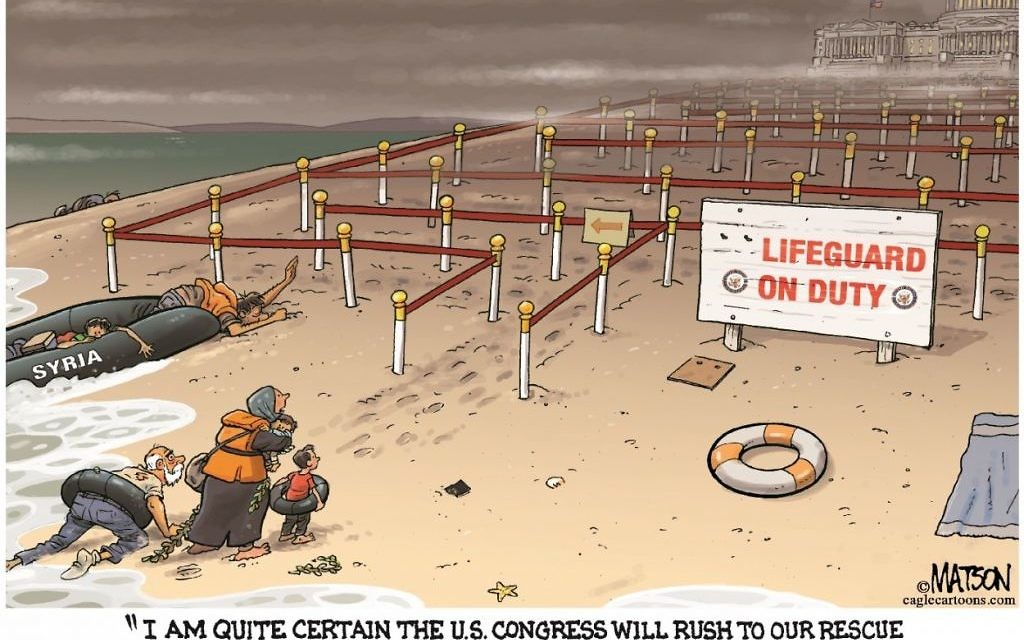

The designated topic, population migration around the world, was chosen a couple of months ago, after the photograph of the Syrian boy washed up on a Turkish beach sparked debate and before acts of terrorism turned that lava flow into a volcanic eruption spewing invective on the campaign trail, on the airwaves and online.

The discussion leader posited that one side considers the issue of resettling refugees in this country primarily as a matter of security while the other regards it primarily as a matter of justice. That does not mean, though, that those concerned about security aren’t also interested in justice or that those interested in justice aren’t also concerned about security.

The rub comes when one side decries the other’s priorities as misplaced or invalid. A better outcome is possible, we were told, if those interested in justice first acknowledge concerns about security and if those concerned about security first acknowledge the interest in justice.

The director of an agency that has resettled thousands of people from oppressed and war-ravaged nations into our community was a guest at dinner. These refugees, who have been vetted in a process that can require more than a year, are grateful to be in America, she said. For now, they want only to find jobs to shelter and feed their families and to educate their children. There is time for them to learn the rough-and-tumble ways of America’s advanced citizenship.

As the political campaign makes your blood boil, keep in mind these words, written a couple of years ago by a real rabbi: “A community’s destiny does not rise and fall based on how it handles its times of harmony and consensus, but on how it responds to its moments of greatest discord and disagreement.”

comments