To Be Held Accountable

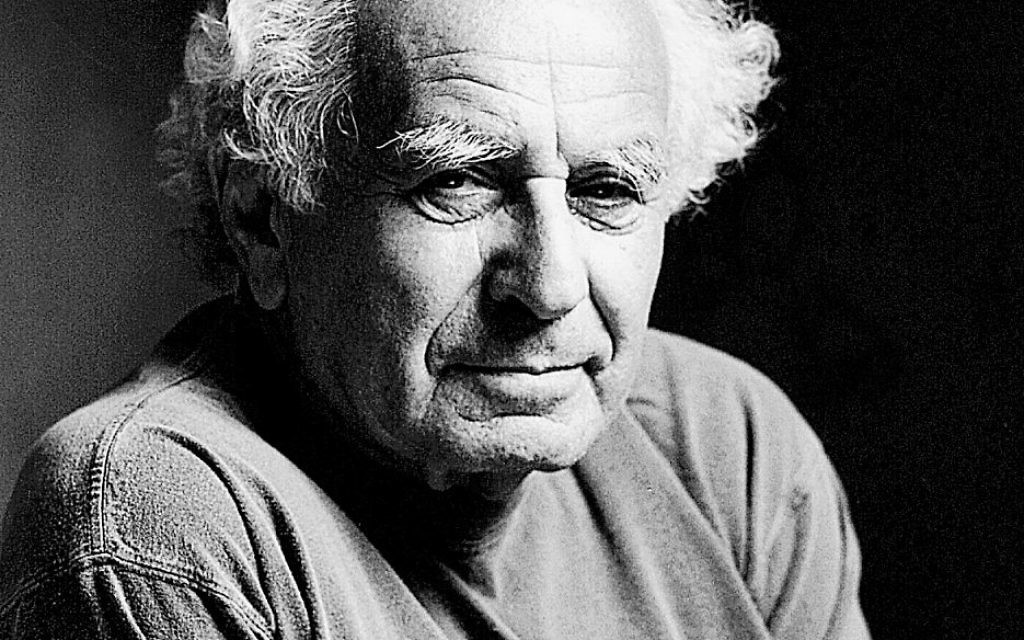

Eugen Schoenfeld was born November 8, 1925. He is the oldest son of a book store owner in a small town in Czechoslovakia and a Holocaust survivor.

As the month of Elul arrived, the mood of Jews in my hometown Munkacs, my erstwhile shtetl in the Carpathian Mountains, drastically changed. Slowly the Jewish population became enveloped in fear. We began adding additional prayers seeking forgiveness for our sins, and the sound of the “shofar” was added to the end of morning prayers as though declaring: “Awaken Jews, the days of awe – the days of judgment are approaching. Be ready to be held accountable for your deeds. Your fate for the next year will soon be written into that big and awesome book.”

Beginning with my early childhood I was indoctrinated to the idea of accountability. This was especially true when I turned 13. And while we were celebrating this rite de passage – my bar mitzvah – I was thrust into adulthood and my father declared before the whole congregation that he is no longer responsible for my sins. This he did with the following statement: “Blessed is He who freed me from the punishment of this one.”

To describe the awesomeness of the 10 days of repentance, I was told about God, who, to me, was that old man with a flowing beard. He had called his heavenly court to order and the dreaded book was brought forth in which we, in our own handwriting, have noted all our deeds of the past year, and, on the basis of our own declarations, we will be judged, punished or rewarded. Behold: This is Rosh Hashanah; this is the Day of Judgment, declared the heavenly choir, for even they were judged and found wanting.

Get The AJT Newsletter by email and never miss our top stories Free Sign Up

The scene in heaven is set. God, as supreme judge, sits on his throne, the deeds in the book read to Him, and both facsimiles of my good deeds are placed on one side of the scale and my bad deeds on the other, and judgment is about to be made. Of course, as it is on earth, so it is in heaven. There are two angels next to me: the Saneygor, my defender, and the Kateygor, my accuser. Of course, this Ezekiel description was both fascinating to me as a young boy, while simultaneously, I was awestruck by it. But, as I entered into my teens, I began to have a critical outlook on what we believed and practiced. The central question that I faced on these holidays: What are we accountable for and to whom are we accountable?

For a long part of our history, Jews considered judgment and accountability associated with Rosh Hashanah applicable to Jews alone. Yet, in small letters, the idea of accountability as a universal moral order is introduced in a prayer recited after the shofar-blowing ceremony. There we state: “On this day He causes all the creatures of the universe to stand in judgment.” This statement told me that the universal God has given us universal principles of right and wrong and we are accountable to ourselves whether we follow these dicta or not.

Following the notion of human universality, I propose that on Rosh Hashanah, this day should become an advocate for the need of a universal day of accountability. After all, isn’t God a universal entity, a God of all people, and the moral laws we advocate in his name, aren’t they the same moral laws that should apply to all people? Isn’t this the conclusion we draw from our Egyptian experience? I have often wondered if other religions would, like Jews do, stress the idea of accountability would there not have been a Holocaust?

The idea of accountability that I was taught in childhood, in an altered form, has remained with me as the central idea of Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. There are two foci regarding the ideals of accountability: what are we accountable for and to whom are we accountable? The traditional perspective proposes that we are accountable for adherence to the 613 commandments and we are accountable to the supreme judge – God. But a more careful reading of texts led me to conclude that God, starting with Adam, turned over the human world to us. When God separated heaven from earth, he also gave us, through Adam, accountability for our relationship to man and to the world we live.

While the Torah details a number of moral dicta, all fall into two moral imperatives: The first is tzar bal chai. That is not to cause pain – physical and emotional – to any living things. This includes the rights to access, to life, to all the means necessary to maintain life through justice. The second universal principle is that God created, by whatever means, a universe that is founded on equilibrium and harmony, and assigned us the task to maintain universal harmony. One of the many poets whose work makes up part of the Hallel (prayers of praise) declares:

The heaven is God’s domain, and the earth He gave to mankind, and charged mankind with the task to maintain his intent of a place in harmony.

The idea of the existence of harmony in nature is to Einstein the sine qua non, evidence of God’s existence, and hence, it should also be central to the human world – a world of our creation. Einstein stated: “I believe in Spinoza’s God, who reveals himself in the harmony of all that exists.” Einstein furthermore believed and declared that to understand God, we must understand the equilibrium and harmony that is essential to understand the universe, for they are the foundation of the laws that govern nature and the universe.

The whole world refused to assume the responsibility that God placed on us – namely, the task to improve the world and to seek the creation of a humane world founded on the unity of mankind, on the principles of justice. The rabbis of the first century placed great importance on the Hebrew concept torchoh (effort). That is, if we wish to have a better and peaceful world, it doesn’t come through prayer, but through our own efforts.

On these two days, on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, the whole world – Jews and non-Jews – should be aware that we, total humanity, like it or not, are held accountable, whether or not we have fulfilled our assigned mission in life. Namely, have we improved the world (the principle of Tikkun) or have we, contrarily, worsened conditions? This idea is symbolically represented by the concept of “the book.” It is a book of accounting and the two-armed scale, a symbol of the function of equilibrium.

Perhaps the greatest of all human tragedies is the rejection of the symbol that signifies the unity of the universe and that is contained in the word echod. We, the Jews, who were the first to proclaim this unity, have lately rejected this idea, and instead, introduced forces of separation and rejection – especially among ourselves. We have rejected the essence that is proclaimed in the declaration of “Shema,” namely, the unity under the symbol of God, the force that is the essence of harmony and justice. And, for this, we must be accountable. Instead, standing and declaring the oneness of God and the unity of mankind, we support contention. As we did way in the past, we must come back to these principles and work for unity of the universe.

comments